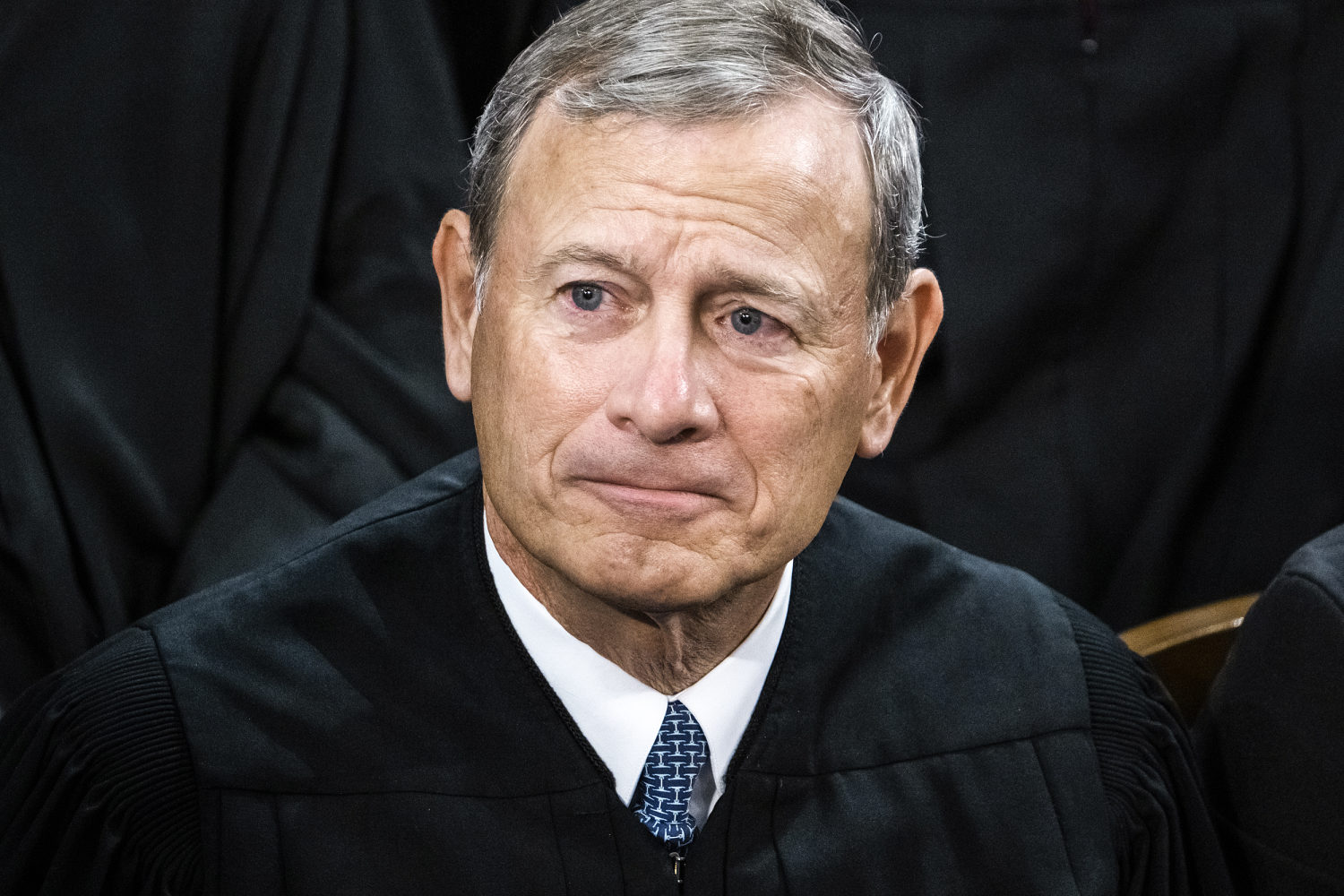

Reading Chief Justice John Roberts’ annual end-of-year report on the federal judiciary is a bit unsettling, and not just because of its enumeration of the very real dangers to this country’s long tradition of judicial independence that we now face. But while Roberts rightly highlighted those threats, he failed to name their source: Donald Trump.

Based on the report, it is hard to know if Roberts sees Trump for what he is. He has had an up-and-down relationship with the president-elect. Often, he has delivered decisions, like last year’s ruling on presidential immunity, that all but bend over backward to please Trump. At other times, he has made public statements defending the fairness of federal judges in response to an unfounded attack by the president-elect.

In the 2024 report, Roberts offers no such defense. Trump is what literary critics call an “absent presence” in Roberts’ 15-page document. He is like a ghost, whose presence is felt if not seen.

Some of what Roberts named might have been best described as a self-inflicted wound.

Aside from the usual statistics on the courts’ workload, the report made news because of what he writes on page 5: “I feel compelled to address four areas of illegitimate activity that, in my view, do threaten the independence of judges on which the rule of law depends: (1) violence, (2) intimidation, (3) disinformation, and (4) threats to defy lawfully entered judgments.”

Some of what Roberts named might have been best described as a self-inflicted wound or perhaps been best addressed to the radical conservatives on the Supreme Court who seem to value loyalty to Trump and the MAGA cause more than their duty to decide cases without fear or favor. Beyond that, the threats that the chief justice mentioned all seem to have their roots in the authoritarian playbook that has guided Trump and his MAGA acolytes. He leaves it to his readers to connect the dots.

Echoing past defenses of judicial independence, Roberts trots out quotations from the Founders and former justices. On page 2, he quotes Alexander Hamilton’s admonition that “there is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers.”

Then, invoking the memory of the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist, for whom Roberts once clerked, the current chief justice writes, “The independent federal judiciary established in Article III and preserved for the past 235 years remains, in the words of my predecessor, one of the ‘crown jewels of our system of government.’”

Roberts also approvingly cites former Justice Anthony Kennedy’s argument that “judicial independence is not conferred so judges can do as they please. Judicial independence is conferred so judges can do as they must…. (It) is essential to the Rule of Law.”

In Trump’s world, court decisions are like elections: fair if he or his side wins, rigged or corrupt if they lose.

Rehnquist and Kennedy believe that the greatest threats to an independent judiciary come from “the other branches of government” that will be tempted to exert “improper influence.” But this understanding lets judges off the hook. The absence of outside influence does not guarantee that judges will be independent and impartial rather than partisan warriors. Judges as partisan warriors seems a fit description for some of the current crop of Supreme Court Justices.

As Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern wrote in July at the conclusion of the Supreme Court’s most recent term, “the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority has, in recent weeks, restructured American democracy in the Republican Party’s preferred image, fundamentally altering the balance of power between the branches and the citizens themselves.”

“The six ultra-conservative justices,” they conclude, “have positioned themselves as partners in Trump’s fight.”

Yale historian Timothy Snyder might call that a form of “obeying in advance.” But whatever we call it, Roberts makes no reference to this particular threat to judicial independence.

As for the four threats he does name, he writes as if they have no common root, despite a mound of evidence to the contrary. Last February, for example, Reuters reported that “Judges and prosecutors are facing repeated threats of violence as they handle cases related to Trump … The wave of intimidation follows the ex-president’s attacks on judges as corrupt and biased.”

It further notes: “Since late 2020, Trump has ramped up his criticism of the judiciary dramatically … serious threats against federal judges alone have more than doubled, from 220 in 2020 to 457 in 2023.”

Reuters also quotes retired Ohio Supreme Court Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor, a Republican, who showed no reluctance to place blame where it belongs. “Donald Trump set the stage… (and) gave permission by his actions and words” for others to threaten violence, try to intimidate and spread disinformation about judges who make decisions of which he disapproves.

In Trump’s world, court decisions are like elections: fair if he or his side wins, rigged or corrupt if they lose. Years of this rhetoric have set the stage for Trump to defy any court decision of which he disapproves once he returns to the Oval Office.

If he wants to do so, he will receive encouragement not just from the MAGA base, but from Vice President-elect JD Vance, who in 2021 approved of just such a scenario: “When the courts stop you,” Vance said, “stand before the country like Andrew Jackson did and say the chief justice has made his ruling, now let him enforce it.”

Clark Nelly, senior vice president for legal studies at the Cato Institute, thinks that Trump will follow President Jackson’s example. “Trump,” he wrote in October, “would be a lame-duck POTUS with good reason to believe he can — again — win a game of impeachment-chicken with Congress. It’s reasonable for him to suppose there would be no practical consequences if he tells Chief Justice John Roberts and company to pound sand.”

Nothing in Roberts’ report suggests that he would be up to that challenge. He did not even have the courage to identify the real threat and the “absent presence” in his text. The chief justice would have served the country better if he had ended 2024 with four simple words: “Stop it, Donald Trump.”