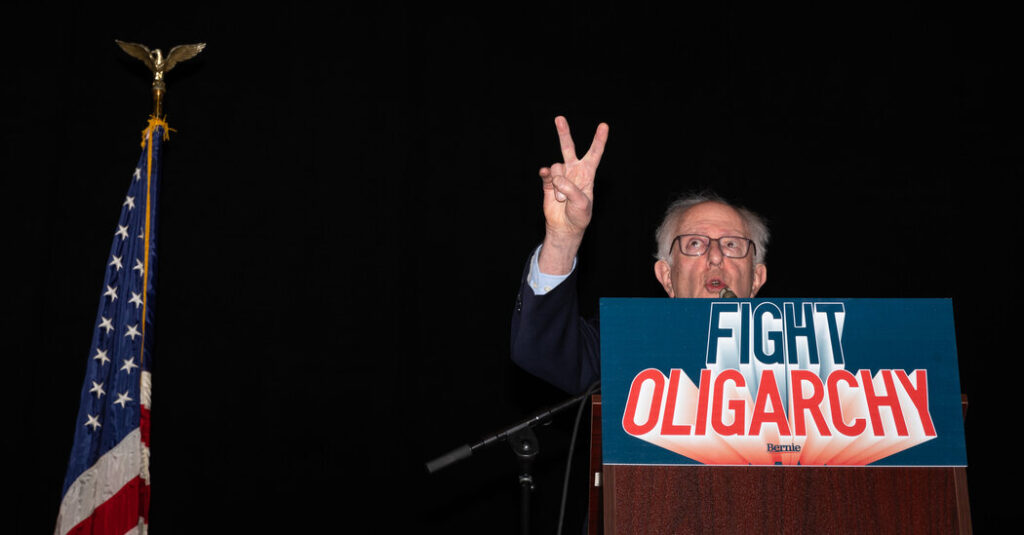

The Democrats, casting about for an anti-Trump narrative, have found a word: “oligarchy.” It was part of Joe Biden’s farewell address; it’s central to Senator Bernie Sanders’s barnstorming; it shows up in the advice given by ex-Obama hands. It aspires to fold together President Trump’s self-enrichment, Elon Musk’s outsize influence, the image of Silicon Valley big shots at the inauguration with a familiar Democratic criticism of the G.O.P. as the party of the superrich.

I don’t want to pass premature judgment on its rhetorical effectiveness. But as a narrative for actually understanding the second Trump administration, the language of “oligarchy” obscures more than it reveals. It suggests a vision of Trumpism in which billionaires and big corporations are calling the shots. And certainly, the promise of some familiar Republican agenda items — like deregulation and business tax cuts — fits that script.

But where Trump’s most disruptive and controversial policies are concerned, much of what one might call the American oligarchy is indifferent, skeptical or fiercely opposed.

Start with the crusade against wokeness and D.E.I., a fight spreading beyond the federal bureaucracy to everything (state policymaking, university hiring) influenced by federal funding. Is this a central oligarchic agenda item? Not exactly. Sure, some corporate honchos were weary of activist demands and welcomed the rightward shift. But before the revolts that began with politicians like Ron DeSantis and activists like Christopher Rufo, the corporate oligarchy was an ally or agent of the Great Awokening, either accepting new progressivism’s strictures as the price of doing business or actively encouraging D.E.I. as both a managerial and a commercial strategy.

Capital, in other words, is flexible. It can be woke or unwoke, depending on the prevailing winds, and it will adapt again if anti-D.E.I. sentiment goes away.

Next, consider Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency, with its frantic quest to slash contracts, grants and head counts at government agencies. Is this oligarchy? No doubt some corporations stand ready to fill spaces left open by the public-sector retreat. But the American corporate sector as a whole is deeply enmeshed with governmental contracting, heavily invested in public-private partnerships, accustomed to cozy lobbying relationships and eager to take advantage of government largess.

So there is no deep corporate investment in reducing head count at random federal agencies, and there is plenty of corporate angst about what DOGE might mean for the specific kinds of private-sector power that have metastasized all around Washington.

And even with Musk himself, the first oligarch: For all the ways he might use his access to game the system, the immediate effect of his crusade has been to undermine Tesla, his most important company, and substantially diminish his (yes, still world-beating) net worth. (The risks to his position if and when Republicans lose power are even more considerable.) So we should take him at least somewhat seriously when he talks like a libertarian or debt-crisis true believer; he’s putting his net worth in the service of those ideas rather than just leveraging power to increase his wealth.

Finally, populist ideas rather than oligarchic self-interest are clearly the motivating factor behind Trump’s highest-risk move, the great tariff experiment. Of course, there is a tycoon who stands to benefit from protectionism out there somewhere, but the generalization still holds: When it comes to the lords of the American economy, nobody wants this.

The people who do want it are the right’s version of the critics of neoliberalism who influenced Biden’s administration: outsider intellectuals and dissenting members of officialdom who see themselves as champions of downscale constituencies ill served by a globalized system designed to benefit investors, corporations and billionaires. There are all kinds of ways in which Trump has failed to follow through on populist promises, but the vision of a new trade order is populism in its truest form; it rejects a consensus shared by academic experts and the upper class, and it promises long-term benefits for the working man in exchange for short-term pain for rich investors.

As such, it can’t really be attacked coherently along the lines favored by Sanders or any left-wing Democrat. It’s not a giveaway to Trump’s biggest donors. (They hate it.) It’s not a sop to the Wall Street players. (They’re against it.) It’s not an intensification of neoliberal capitalism but a rejection of its premises.

Instead, the opportunity it offers Democrats, like the opportunity that Biden’s attempt at postneoliberalism offered Republicans, is contingent on its actual economic effects. A future where the economy sputters even as Muskian cuts lead to foul-ups with popular government programs offers Democrats the clearest path back to power. But they won’t be leading a revolution against the oligarchy; they’ll be promising a restoration.