Mitch McConnell will end his Senate career with his most indelible mark on the nation’s federal courts and the chamber’s judicial confirmation process, a priority that changed the chamber’s rules and solidified a conservative Supreme Court for the foreseeable future.

As majority leader during the last two years of President Barack Obama’s presidency, McConnell used his control of the Senate to slow judicial confirmations to all but a trickle. He also led his party to leave open for months a Supreme Court vacancy left by the Feb. 2016 death of Justice Antonin Scalia, when Obama’s pick of Merrick B. Garland would have given a liberal tilt to the high court.

And then Donald Trump won the 2016 election. McConnell made judicial confirmations his top priority and changed the Senate filibuster rules to lower the threshold needed for Supreme Court nominees. That mirrored a rule change on lower-court nominees made in 2013 by the previous majority leader, Harry Reid, D-Nev., which Republicans took advantage of to sweep in Trump’s other judicial picks at a record pace.

Those judicial appointments, particularly to the Supreme Court, have caused huge swings in American law, from overturning the federal right to an abortion to expanding gun rights and giving themselves more power to scrutinize federal agencies. And it gives conservatives a lasting advantage in the nation’s courts.

“There’s no question that he is single handedly responsible for the constitution of the Supreme Court right now,” Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, said. “I don’t think you could overstate just what an impact he has as an individual. More than anybody’s walked around D.C. over the last 10 years that I’ve been here.”

Sen. Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, said he respects McConnell and his service to the country, but that it had a negative impact on the judiciary. “Mitch stacked the courts, I know him well enough to know he considers that a gold star, but I consider that a blemish,” Schatz said.

It all flowed from the Kentucky Republican’s focus on courts. Only weeks before his retirement announcement Thursday, McConnell told “60 Minutes” that he focused on lifetime judicial nominations because changes in which party controls Congress means “normal legislative activities” have less of a lasting impact.

“I felt that the way to get lasting impact is to put the right kind of men and women on the courts who hopefully will be there for a while,” McConnell said.

Trump was able to appoint a total of 234 federal judges, including 54 appellate judges, shepherded through the process by McConnell. During a September 2020 presidential debate, Trump said that his judicial confirmations were “maybe the most important” thing about his first term.

In 2018, then-White House Counsel Don McGahn told a gathering of conservative lawyers that McConnell orchestrated the opportunity for Trump to reshape the courts with conservative judges by blocking Obama’s judicial picks and leaving Trump with a large number of judicial vacancies to fill.

“He has made this his No. 1 priority, and he has delivered,” McGahn said.

Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, said that McConnell’s work frequently emphasized confirming judges, something Democrats modeled during the Biden administration.

“He pointed out a lot of these nominees that we were considering, were not going to serve more than a term, but these judges are people that serve literally the rest of their professional lives,” Cornyn said.

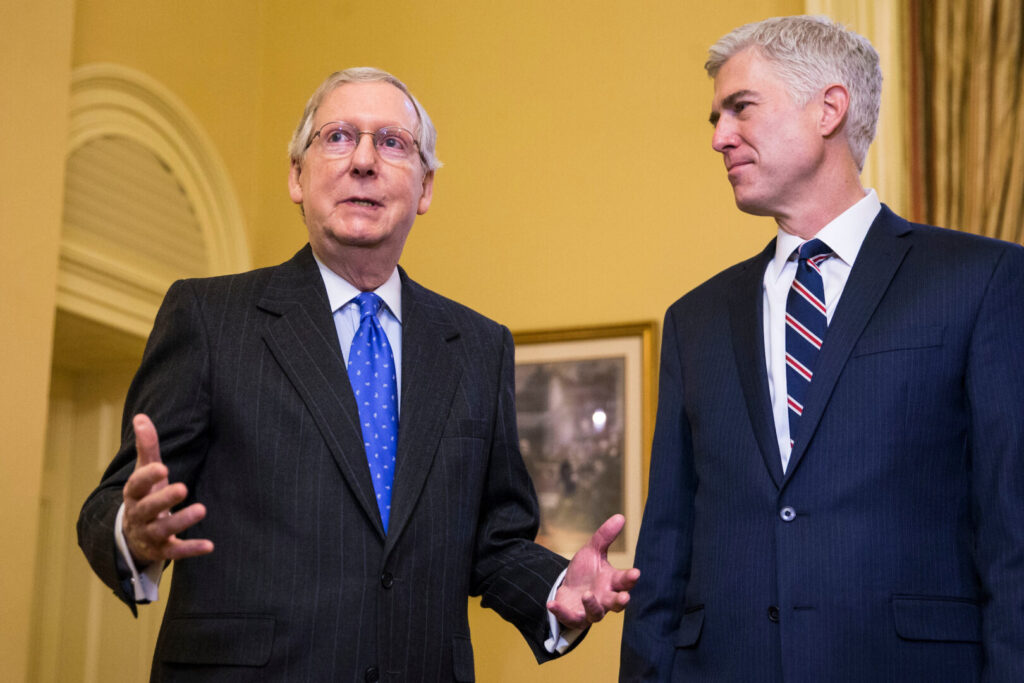

During the first Trump administration, the McConnell-led Senate confirmed Justices Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, each with their own controversy and drama that maxed out the meters of partisanship.

Cornyn said he particularly recalled working as majority whip with McConnell during the confirmation process for Kavanaugh, where they held meetings with individual senators who “had questions” about Kavanaugh’s nomination.

“A lot of these were very close calls and Brett Kavanaugh ended up getting confirmed,” Cornyn said.

McConnell led Republicans as they confirmed Barrett only days before the 2020 presidential election, filling a vacancy left by the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and moving the high court to a 6-3 conservative majority.

Democrats decried what they called a hypocritical and sham confirmation process when compared to the block of the Garland nomination ahead of the 2016 election. Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer of New York at the time dubbed it a “partisan theft of two seats on the Supreme Court using completely contradictory rationales.”

“The truth is, this nomination is part of a decadeslong effort to tilt the judiciary to the far right to accomplish through the courts what the radical right and their allies, Senate Republicans, could never accomplish through Congress,” Schumer said on the Senate floor.

At the swearing-in ceremony for Barrett, just days before the 2020 election, Trump said: “Our country owes a great debt to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.”

Campaign finance

McConnell’s focus on a lasting impact also showed in his yearslong effort to prevent an overhaul of campaign finance law. Once he lost that fight in Congress, McConnell went to the courts to stop the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act — the 2002 law also known as the McCain-Feingold law for its principal sponsors, the late Sen. John McCain and former Sen. Russ Feingold.

The same day it was signed into law, McConnell filed a challenge on free speech grounds and was the named plaintiff at the Supreme Court. In that case, the justices would rule 5-4 ruling in McConnell v. Federal Election Commission to uphold the law’s main provisions — a ban on “soft money” to political parties and restrictions on political ads by outside groups.

But McConnell kept supporting challengers in subsequent free speech cases at the Supreme Court that would later curtail campaign finance restrictions. In a 2022 case brought by Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, McConnell filed a brief that urged the court to wipe out the BCRA entirely.

“There is no reason to let BCRA limp along, no need for further piecemeal surgery by this Court: the Court should strike the entire statute,” McConnell’s brief stated.

Although McConnell’s partnership with Trump helped him shape the courts, the pair have a publicly rocky relationship.

Numerous times over the years, the pair publicly criticized one another. During Trump’s second impeachment trial after the 2021 attack on the Capitol, McConnell blamed Trump for the attack but ultimately argued against conviction.

“We have a criminal justice system in this country,” McConnell said at the time. “We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being held accountable by either one.”

Ultimately the Supreme Court, including the three justices McConnell helped confirm, ruled last year ahead of Trump’s victory in the election that Trump was immune to most criminal charges.

McConnell’s influence will continue long after he leaves the chamber — and it could even grow. He ushered a young Kentucky lawyer, Justin Walker, onto a federal appeals court in Washington often referred to as the second-most-important court in the country.

It’s one where presidents often look for potential Supreme Court nominees.