On the day that Pete Rose was banned from baseball in August 1989, Major League Baseball Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti did something that is impossible to imagine today.

He stood in front of a horde of reporters at the New York Hilton in midtown Manhattan. He looked into a bank of television cameras beaming his news conference live into living rooms nationwide. He gave a short and poetic statement, announcing Rose’s permanent banishment from the game and the reasons for it, and then Giamatti took the reporters’ questions for about 45 minutes — on live television.

In this moment, he didn’t feel like a commissioner of a major American sport; he looked like himself — a former professor at Yale University, lecturing on a subject he loved: baseball.

“I will be told I am idealist,” Giamatti said that day. “I hope so.”

In some ways, Rose never fully reckoned with his actions before his own sudden death last fall.

He thought it was important to find ideals in baseball — “the national game,” he called it — and to protect these ideals at all costs. But he also believed in something else. Giamatti said that day in New York that Rose’s name would appear on the ballot for baseball’s Hall of Fame, as scheduled, in 1991 — five years after Rose’s last at-bat as a player. Though Rose had bet on his own baseball games, risking the integrity of the game and violating its best-known rule, Hall of Fame voters would have a chance to cast a ballot for Rose.

“You have the authority,” Giamatti told the reporters that day, “and you have the responsibility, and you will make your own individual judgments.” Frankly, Giamatti said, he was looking forward to seeing how the writers sorted through what he called “the relationship of life to art — which you will all have to work out for yourselves.”

Within days of the announcement, Giamatti died suddenly of a heart ailment. Two years later, the National Baseball Hall of Fame changed the rules, removing ineligible players, like Rose, from the pool of potential candidates. For the next 15 years, Rose continued to lie about what he had done, refusing to admit he had bet on baseball. Those lies hurt lots of people, including his family, his friends, his teammates, people in his hometown of Cincinnati, and the memory of Bart Giamatti. And in some ways, Rose never fully reckoned with his actions before his own sudden death last fall. Like a lot of addicts, Rose never fully got right with the world.

But 36 years after Giamatti’s news conference, Commissioner Rob Manfred will finally let at least a few Hall of Fame voters have that debate that Giamatti wanted. On Tuesday, Manfred ruled that a player’s ineligibility ends at his death, thereby removing Rose, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and 15 other disgraced men from baseball purgatory. By rule, starting in 2028, Rose could now be voted into the Hall of Fame by a small committee that takes up the cases of players who competed long ago.

It’s a significant policy change for baseball and it threaded an impossible needle. In making his announcement, Manfred gave Rose’s loved ones and maybe President Donald Trump what they wanted, without having to promise anything else. But Manfred’s choice has also turned a long hypothetical debate into a real and raging one: Does Pete Rose deserve to be in the Hall of Fame? As usual with Rose, it’s complicated.

Maybe it’s time we stopped pretending that every great baseball player also happens to be a moral person.

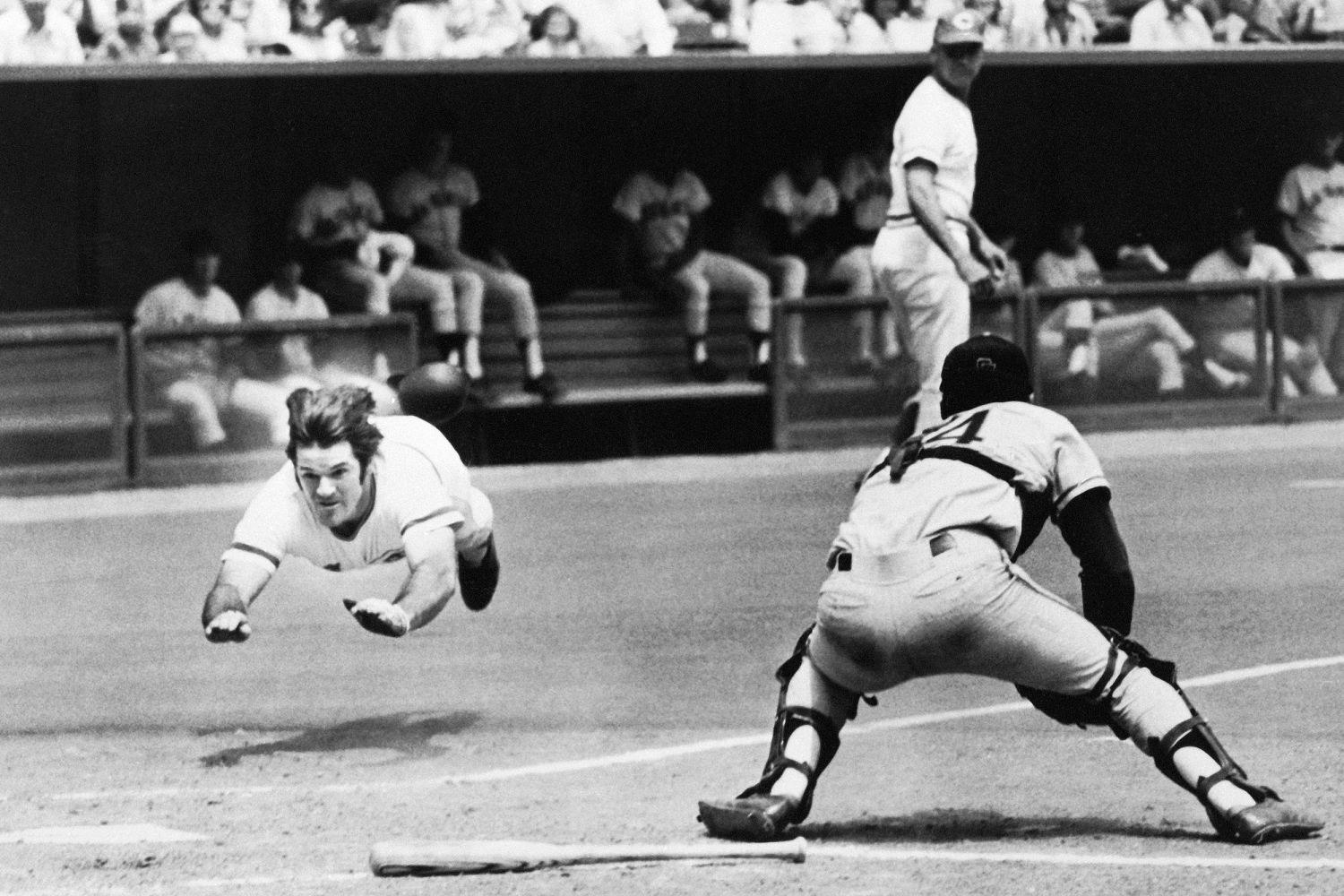

On the one hand, he compiled more hits in baseball history than anyone else — 4,256 — and he did so while playing the game in an iconic fashion. Fans loved how Rose sprinted to first base on a walk, slid headfirst into third, barreled into catchers trying to block home plate, and fought with shortstops out at second — anything to win. This approach earned him the nickname “Charlie Hustle” and the name alone endeared him to us. He was the American dream, rounding third. So, of course, defenders say, Rose deserves to be in the Hall of Fame.

But while we were cheering for him, Rose was making grave mistakes off the field. As I learned in the reporting for my book, he ran with gamblers and bookies. He cheated on his wives. He had an affair with a teenage girl in Cincinnati in the 1970s. He lied about all of it. And by at least 1986, he was betting on his own baseball games and incurring massive debts to bookies on the fringes of the mob. These debts, without question, put the game at risk and made Giamatti’s fraught decision easy: Pete Rose — trapped inside his lies and his addictions — had to go. So, of course, critics say, he deserves nothing, except for what he got: his banishment.

The people on that committee at the Hall of Fame now inherit this thorny debate, and as a baseball fan and a historian, I’ll be interested to see what they do. But I also happen to think it’s the wrong debate.

We like to put our favorite athletes on pedestals and ascribe moral values to them. The truth is, we don’t know much about them at all. And we’ll know even less about our favorite players going forward, in a time the most famous athletes live inside gilded bubbles, protected from journalists and fans by legions of handlers.

So maybe it’s time we stopped pretending that every great baseball player also happens to be a moral person. Maybe it’s OK to acknowledge that they were just talented at playing a little kid’s game. And maybe we should consider enshrining their mistakes along with their accomplishments. We could put their shortcomings in bronze too — for perpetuity.

Under this format, there’d be a lot of interesting plaques to read at Cooperstown. The Hall of Fame already includes a long list of miscreants: gamblers, alcoholics, drug users, adulterers, cheaters, spitballers, ball scuffers, liars, deadbeats, racists, and at least two hitters once accused of conspiring to throw games for money.

They’re all there. Not great.

Just really good at baseball.