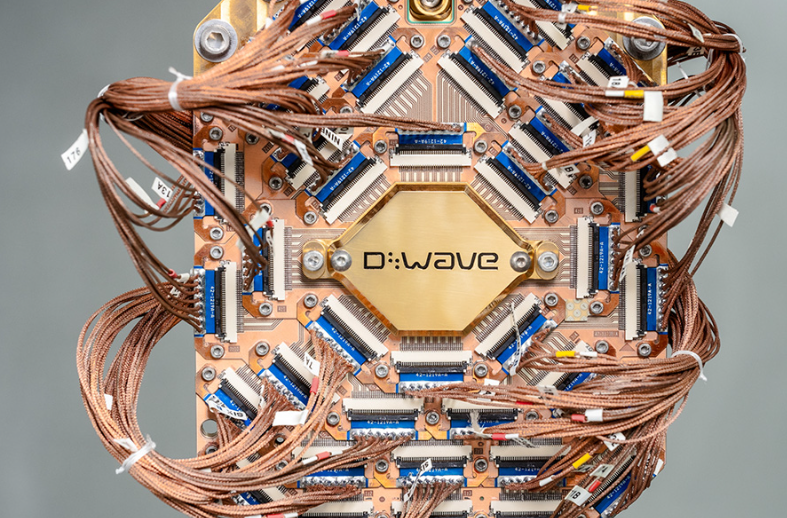

D-Wave Quantum Inc. said today a peer-reviewed scientific paper proves it has finally passed a critical threshold and achieved “quantum supremacy” — that is, the point at which its quantum computers have finally solved a problem that’s impossible for even the most powerful “classical” computers to do.

The paper, published in the journal Science on Wednesday, shows that the company has finally achieved the “Holy Grail” in quantum computing, D-Wave Chief Executive Alan Baratz said in an interview with the Wall Street Journal. “This is what everybody in the industry has been aspiring to, and we’re the first to actually demonstrate it,” he said.

Quantum computers are different from classical systems because they use quantum bits, or qubits, which can exist in two states at once. They can be both ones and zeroes, whereas regular “bits” can only be either a one or a zero, but not both at the same time. This unique ability allows quantum computers to crunch numbers at truly enormous scales, vastly outperforming the capabilities of traditional computers, and paving the way for new applications in fields such as drug discovery, genetics and materials research, among others.

That said, building quantum computers that can scale to a point where they become useful has proven to be extremely challenging, and D-Wave and rivals such as Google LLC and IBM Corp. have struggled for years to get there. To obtain an advantage over its competitors, D-Wave opted to work on a more limited architecture based on “quantum annealing,” which is suited to a narrower range of optimization problems and materials simulations.

The company says this approach makes D-Wave’s systems more suited for calculations such as the “traveling salesman” problem, which involves finding the optimal route among a vast number of different locations, and therefore suitable for certain kinds of business applications.

In the paper in Science, D-Wave said it has solved a problem relating to the simulation of materials with a complex magnetic field with extremely high detail in about 20 minutes. It says it would take the most powerful classical supercomputer almost 1 million years to reach the same outcome.

Baratz argues that this represents the first time that a quantum computer has shown itself to be superior to classical machines in a kind of problem that has practical business uses. The ability to simulate new magnetic materials can help advance multiple industries, allowing their properties to be fully understood before they’re produced.

Results disputed

However, a number of academics have come forward to dispute D-Wave’s claims already. New Scientist reported that Dries Sels and his colleagues at New York University were able to perform similar calculations on a regular laptop in just two hours, using a mathematical technique known as “tensor networks,” which reduce the amount of data required for simulations, meaning they can perform them with a lot less energy.

D-Wave Senior Distinguished Scientist Andrew King told the New Scientist that Sels’ results don’t change anything.

“They didn’t do all the problems that we did, they didn’t do all the sizes we did, they didn’t do all the observables we did, and they didn’t do all the simulation tests we did,” he insisted. “They’re great researchers, but it’s not something that refutes our supremacy claim.”

King added that after hearing about Sels’ work, he decided to scale up the quantum computer’s calculations to use up to 3,200 qubits, which is far beyond the 54 simulated by Sels. According to him, the results of that experiment reinforce D-Wave’s supremacy claims, but the results of that research have not been published.

Sels retorted that King’s response is “petty” and explained that he could easily scale his tensor-based approach to achieve the same results. He added that the time it takes to run the algorithm scales linearly based on the size of the problem, so there’s no real need to test larger problems.

In another response to D-Wave’s paper, quantum researchers Linda Mauron and Giuseppe Carleo at École Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne, Switzerland, told New Scientist that the problems the company solved can in fact be tackled without any need for quantum entanglement. There’s no need even to simulate the effects of quantum entanglement with a classical computer, they added.

Having heard about D-Wave’s claims, they rushed to publish their own paper, which showed they were able to tackle the same problem using an ordinary computer powered by just four graphics processing units in three days. As such, they dispute D-Wave’s claim it would take the world’s most powerful supercomputer a million years to perform the same computations.

Once again, D-Wave hit back, responding that while Mauron’s and Carleo’s paper does appear to be an advance, it “does not challenge our claims whatsoever beyond classical quantum simulation.”

D-Wave isn’t the first company to make disputed claims of quantum supremacy. Google did so back in 2019, and its results were similarly challenged by academics, who demonstrated that a traditional supercomputer could be programmed to solve the same problem in much less time than Google said it would take.

That may explain why D-Wave’s paper used the term “quantum advantage” rather than “supremacy,” suggesting it has demonstrated only a marginal improvement over classical machines. However, even a marginal gain could have important implications.

D-Wave is notable for being one of the first quantum computer manufacturers to sell its machines commercially, but it has struggled to build a profitable business. It sold its first quantum computer 14 years ago to a consortium that included Google and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, but later switched focus to making its quantum computers available as a cloud service. Since then, it has picked up customers such as Japan’s leading telecommunications firm NTT Docomo and Canada’s Pattison Food Group Inc.

In 2022, the company racked up a loss of more than $540 million, and its management admitted that it may have to shut down its business if the situation didn’t improve. However, it then bounced back as investors began pouring cash into quantum computing startups, raising $175 million late last year via the sale of equity to private investors.

Despite its struggles, Franz told the Journal, the quarter of a century it has spent building its business is not excessive, noting that it took decades to commercialize classical computers after the emergence of the first transistors.

Photo: D-Wave

Your vote of support is important to us and it helps us keep the content FREE.

One click below supports our mission to provide free, deep, and relevant content.

Join our community on YouTube

Join the community that includes more than 15,000 #CubeAlumni experts, including Amazon.com CEO Andy Jassy, Dell Technologies founder and CEO Michael Dell, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger, and many more luminaries and experts.

THANK YOU